SARS: a glimpse at novel pathogen outbreak potential in the modern world

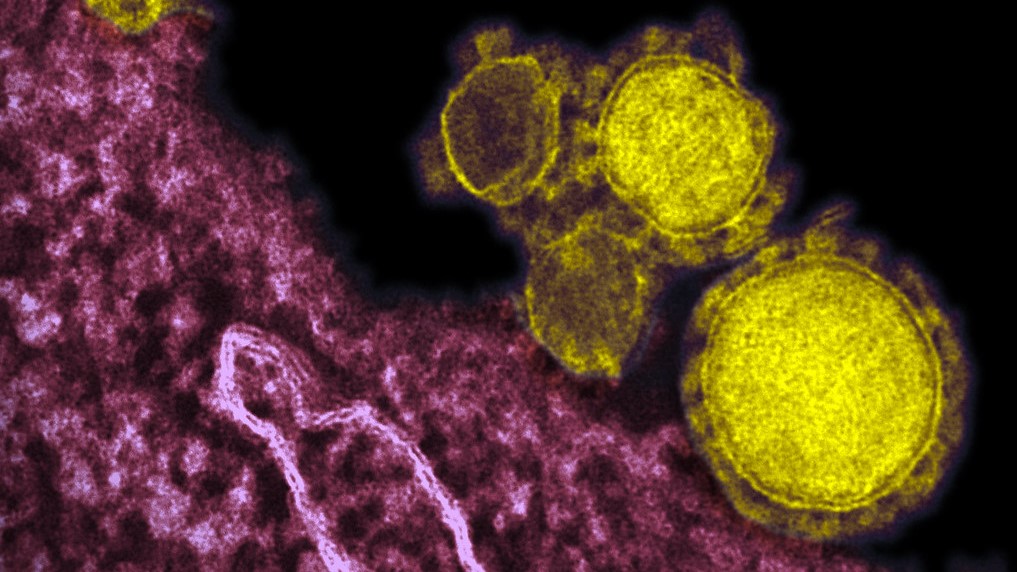

Before 2003, only two relatively simple coronaviruses were known to affect humans and generally caused nonfatal flu-like symptoms. In terms of public health concern, coronaviruses were not highly placed. The family of viruses, though, were well known to affect many animals with varying levels of severity. Then, in November 2002, unusual cases of “atypical pneumonia” started to be reported in Foshan City in Guangdong province, China. This was the start of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic which would go on to cause 8,096 reported cases of illness including 774 deaths in 29 countries and regions, including the United States and Canada. The WHO declared the epidemic over in July 2003, and there have been few cases since.

By March 2003, the cause of the illness was confirmed to be a novel strain of coronavirus, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. The SARS coronavirus likely crossed over to humans from wild animals in Chinese wet markets that sold dead and alive animals in open spaces. This was supported by the findings of the similar coronaviruses in masked palm civets (a small mammalian species) sold in the markets and evidence of SARS infection in their handlers that didn’t cause symptoms. Other studies also found SARS-like coronaviruses in Chinese horseshoe bats. The most significant features of the virus was its ability to efficiently spread through respiratory droplets and potentially in an aerosolized form paired with a high case fatality rate. This became especially problematic in hospital settings with shared air systems and close quarters; a case at a hospital in Toronto led to chains of transmission that involved 257 people and a similar situation at a hospital in Hong Kong led to 138 cases, many of whom were healthcare workers.

The SARS epidemic highlighted significant gaps worldwide in the capacity of public health, medical, and scientific community to deal with outbreaks. In China, the country heaviest hit by the virus, the first public notification about the outbreak from health officials didn’t occur until February 11, 2003, months after the first cases. By that time, there were already hundreds of cases and the public was panicked. “The outbreak caused the most severe socio-political crisis for the Chinese leadership since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown," wrote Dr. Yanzhong Huang of John C. Whitehead School of Diplomacy and International Relations in 2003. Hospitals around the world were faced with inadequate protocols for dealing with a virus like SARS, and the need for improvement in coordination of a multinational health system outbreak response was apparent.

Infectious Disease Clinics of North America

National Academy of Sciences

MERS: another coronavirus making a species leap

The first reported case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) occurred in Jedda, Saudi Arabia on June 13, 2012. A patient presented to a hospital with fast developing pneumonia and kidney failure. The case resulted in an outbreak of infections, especially in health workers having direct contact with the patient. A previously unknown coronavirus was isolated from the patient’s saliva and mucus. Then, in September, the same virus was detected in a patient with a severe respiratory disease who had been traveling in the Middle East Gulf region, and soon thereafter a cluster of pneumonia cases among healthcare workers in April 2012 was traced to the virus. Sporadic outbreaks of the virus continued to occur, and to this day there have been at least 2,292 confirmed cases in 27 countries with a mortality rate of 34%.

Every outbreak of MERS has been traced to travel in the Middle East. Current evidence supports that dromedary camels are a reservoir for the virus and that transmission to humans can happen through either direct contact with the animals or through indirect routes such as drinking their milk. The MERS coronavirus seems to be less contagious than the SARS virus in terms of human to human contact, and generally needs close contact, such as what occurs between healthcare workers and patients, though it is still capable of longer airborne transmission. The resulting disease, however, kills a higher proportion of those affected than SARS.

The health system response to MERS, especially in the early stages, was far from perfect. In Saudi Arabia, some experts reported that poor communication and a lack of accountability in government departments, inadequate state oversight and a failure to learn from past mistakes led to cases being not reported and outbreak responses hindered. In South Korea, a 2015 outbreak infected 86 people, killing 36, and resulted in the quarantine of thousands. Breakdowns in communications between healthcare facilities and personnel and ineffective day to day hospital protocols limiting infectious disease played a part in allowing the outbreak to grow so large. In spite of these failures, many lessons learned from the SARS epidemic were not forgotten by the time MERS appeared, especially the importance of rapid international response to each outbreak. Combined with the lower human to human infectious potential of MERS, outbreaks have generally been limited.

American Public Health Association

World Health Organization

New coronavirus: same mistakes?

Illness from a new coronavirus started appearing among people who were exposed to wildlife at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China. The first cluster was reported on December 31. The city has about 9 million residents and is located halfway between Beijing and Hong Kong. As of Wednesday, January 23, the Word Health Organization reported at least 555 cases and 17 deaths, including cases in the United States, Thailand, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao and South Korea. Like SARS and MERS, the virus seems to be able to cause a range of illness from only mild flu symptoms to serious pneumonia, systemic disease, and death. Though human to human transmission has been confirmed, the extent of its ability to spread through direct contact and through air and the environment is not clear yet.

In some respects, the response to this coronavirus outbreak in China is vastly improved from the SARS response. Chinese President Xi Jinping called for “all-out efforts” to stop the virus’s spread. Local governments were ordered to identify and report cases and to work with the World Health Organization, according to the country’s health ministry. Within about a week of the first reported case cluster, the new virus was isolated and its sequence uploaded to a global network to allow for international diagnosis and research. As of Thursday, January 23, travel bans and disease prevention protocols for Wuhan and several nearby cities were being put into place by the Chinese government to stop disease spread within and from the area.

Not all are happy with the Chinese government’s response, though. Dr. Guan Yi, a professor of infectious diseases in Hong Kong and SARS expert said in an interview that the local Wuhan government was reacting too slowly and hampered his efforts to find the origin of the outbreak. He was shocked to see residents at a market in the Wuhan region not taking any precautions or wearing masks on Tuesday. No additional measures were in place at the airport to disinfect surfaces and floors, either. Both findings were contrary to what the central government in Beijing had ordered. “I consider myself a veteran in battles,” he said, having experience with bird flu, SARS, and other outbreaks. “But with this Wuhan pneumonia, I feel extremely powerless.” In Wuhan, residents are reporting being turned away from hospitals and being refused tests for the virus, with some doctors telling them there is a shortage of tests and hospital beds. “I’m willing to accept that we have to stay in Wuhan, O.K., but the medical care needs to keep up,” one Wuhan resident said. “You shouldn’t tell us we can’t leave, and then give us second-rate medical care. That’s unfair.”

Some are concerned the reasons behind under testing stretches beyond test shortages and into purposeful under reporting of cases and minimizing perception of how serious the outbreak is. Chinese state media has also notably kept coverage of the outbreak to a minimum. On Wednesday, China Central Television left the outbreak as a footnote in its broadcast and on Thursday the front page of the People’s Daily featured President Xi “visiting and comforting” villagers at a “warm and peaceful scene” in a southwestern province ahead of the Lunar New Year holiday. These efforts could be attempts at preventing panic but also serve to limit criticism of the government’s response.

Internationally, governments and health institutions are monitoring travelers from the Wuhan region and gearing up their outbreak response and prevention systems. In Canada, health officials are especially sensitive to the need for an effective response as they remember the outbreak of SARS at a Toronto hospital. “I think people are more knowledgeable, and it’s a totally different world now in terms of how people with respiratory issues are handled,” said David Fisman, an infectious disease expert and professor at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. “This is our stress test. Did we learn enough from SARS to not drop the ball this time?”