This webpage serves as a resource to build awareness of the implications for antimicrobial resistance (AMR), through examining the case of multi-drug resistant Salmonella.

New research between the University of Minnesota and the Minnesota Department of Health aimed to identify and characterize mechanisms for resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella in Minnesota. This research is in keeping with CAHFS's mission to partner to promote a safe and secure food supply, while protecting the health and wellbeing of animals, humans, and the environment.

Below, we use those lenses to examine the challenge of AMR and its importance to the food system, and in particular animal producers and food animal veterinarians.

Educational content developed by Cristina Zarama, MPH student

Salmonella

Salmonella is a type of bacteria associated with foodborne illness, which causes illness in humans and animals.

Antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a naturally ocurring phenomenon in microorganisms.

Multi-drug resistance

Multidrug resistance occurs when microorganisms are resistant to multiple antibiotics or antimicrobials.

Antimicrobials / Antibiotics

As bacteria become resistant to more antimicrobials, treatment options decrease.

AMR in humans, animals, and the environment

One Health is a multidisciplinary approach to achieving optimal health for animals, humans, and the environment. Currently, we are facing a global public health crisis as antimicrobial resistance becomes more widespread. Addressing this public health crisis requires a multidisciplinary approach.

The three videos below explore the topic of antimicrobial resistance from the perspective of each branch of the One Health triad.

AMR and animal health

In this video, Noelle Noyes, DVM, PhD, shares key considerations for AMR and animal health, including what veterinarians and animal health stakeholders can do to combat the emergence of AMR.

AMR and human health

In this video, Craig Hedberg, MPH, PhD, discusses how the public is contributing to the increase of AMR emergence, and what public health professionals can do to prevent further increase.

AMR and environmental health

In this video, Irene Bueno Padilla, DVM, MPH, PhD, speaks to the impact of AMR in the natural environment and the factors that facilitate its transmission.

Salmonella is a genus of bacteria that is composed of two main species: S. enterica and S. bongori, the former being most important in human and animal health. Salmonella species are intracellular pathogens with certain serotypes being pathogenic to humans and animals. Broadly, there are two main disease causing serotypes: typhoidal Salmonella and nontyphoidal Salmonella. Typhoidal serotypes are most commonly associated with diseases such as typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever. Nontyphoidal serotypes are most commonly associated with food-borne infections (i.e. salmonellosis). In the United States each year, it is estimated that 1.2 million human illnesses, 23,000 hospitalizations, and 450 deaths are caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella strains. The focus of this webpage is nontyphoidal Salmonella.

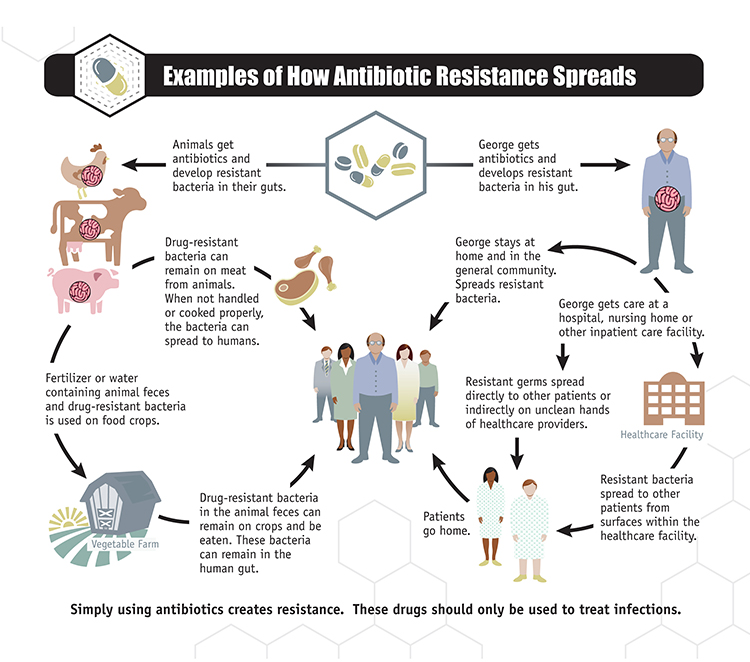

Nontyphoidal Salmonella is spread mainly via the fecal-oral route, through ingestion of contaminated foods, direct animal contact, and rarely it can be transmitted person-to-person. Most human cases are associated with consumption of contaminated foods (beef, poultry, eggs, and milk) and water. Currently, most control efforts aim to reduce infections in poultry and other livestock as they are the major reservoir for human salmonellosis events.

Antimicrobial Resistance and Multidrug Resistance

In 2016 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that antibiotic-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella caused about 6,200 infections in the United States annually. In all likelihood this number has increased since then, since antimicrobial resistance has, in general, been becoming more of an issue in the past years.

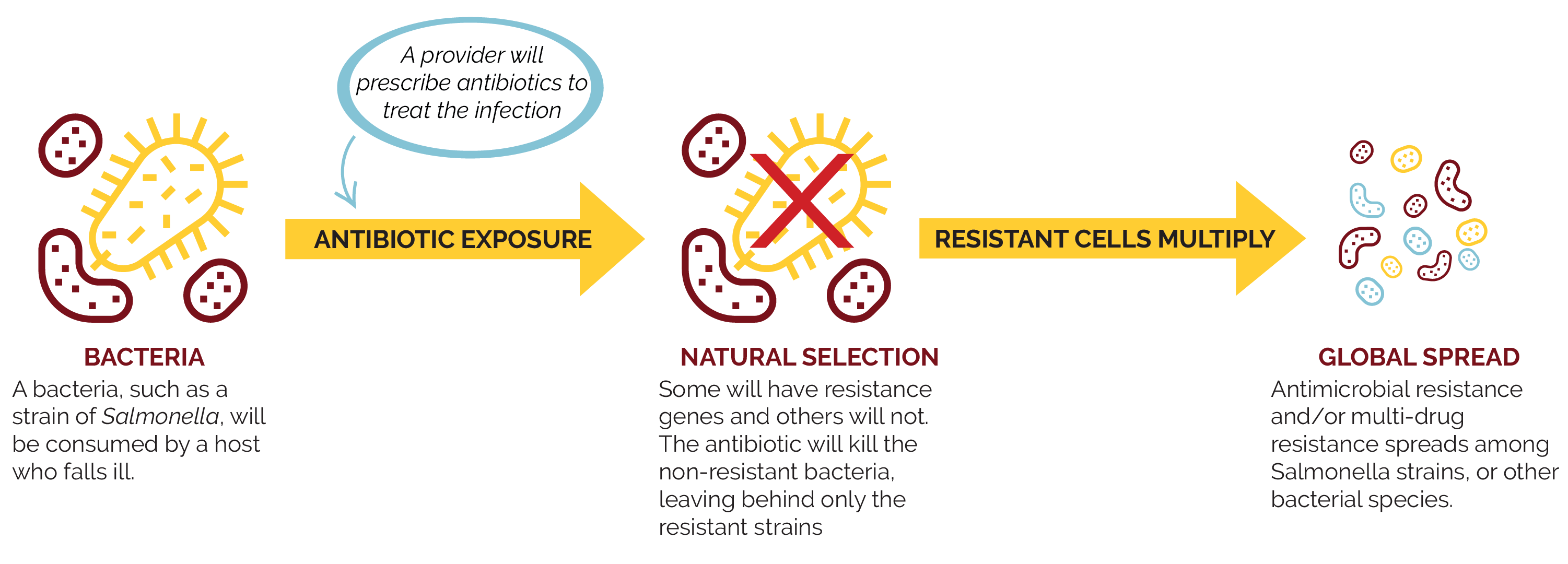

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a natural phenomenon that has been occurring for millions of years. Although the development of antimicrobial resistance is a naturally occurring phenomenon, it is a phenomenon we are encouraging and accelerating through imprudent use of antimicrobials.

There are two main pathways through which AMR can be acquired.

|

Random mutations Random mutations can occur in the genetic material (DNA) of bacteria. Sometimes these random mutations will confer resistance against certain antimicrobials. |

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) Bacteria with AMR genes can transfer these genes to naive or susceptible bacteria. Sometimes bacteria can acquire multiple resistance genes |

Multi-drug resistance

Under the process of HGT, it is possible for bacteria to acquire multiple resistance genes thereby protecting them from multiple classes of antimicrobials. When this occurs, this is an example of multidrug resistance, or MDR.

Multidrug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strains are typically resistant to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, and trimethoprim plus possibly others (Rowe et al, 1997).

As AMR and MDR continue to spread among Salmonella strains and other bacterial species, the burden of disease caused by these pathogens will worsen.

The following graphic demonstrates one simple scenario of how AMR can develop and spread.

Antimicrobials

There is no doubt that antimicrobials have revolutionized the world in which we live. Previously incurable and/or fatal diseases no longer instill fear thanks to the availability of antimicrobials.

Unfortunately, we have reached a point in which “antibiotics have become a victim of their own success” (WHO, 2015). As more and more bacterial diseases confer resistance to one or more classes of antimicrobials, our treatment options will decrease. Unless action is taken, we will regress to a pre-antimicrobial era and AMR and MDR will become as threatening as the diseases themselves once were.

A number of researchers at the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) are currently investigating the threat posed by AMR and, specifically, topics on emerging multi-drug resistant Salmonella strains.

For example, researchers from the CVM and CAHFS analyzed non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates of swine origin from the midwest U.S. to assess the serotype and AMR distribution. This study demonstrated the variation and change over time in Salmonella serotypes isolated from swine clinical samples, and noted an increase in the proportion of the emerging multidrug resistant S. 4,[5],12:i:- serotype. These findings suggested that the reported increase in the frequency of isolation of the S.4,[5],12:i:- serotype in humans may be paralleled by a similar increase in swine clinical samples.

Publications

Elnekave, E., et al. (2018). Salmonella enterica serotype 4,[5],12:i:- in swine in the United States Midwest: an emerging multidrug-resistant clade. Clinical Infectious Diseases; 66(6): 877-85. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/66/6/877/4561545

Elnekave, E., et al. (2019). Circulation of plasmids harboring resistance genes to quinolones and/or extended spectrum cephalosporins in multiple Salmonella enterica serotypes from swine in the United States. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 63(4). https://aac.asm.org/content/63/4/e02602-18.abstract

Hong S., Rovira A., Davies P., et al. Serotypes and antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica recovered from clinical samples from cattle and swine in Minnesota, 2006 to 2015. PLoS One 2016; https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0168016

Outreach

National Hog Farmer: Emerging Salmonella isolated from Midwest Swine (February 2017).

In addition, a number of posters and presentations have been developed on this topic.

Photo courtesy of the National Pork Board, Des Moines, Iowa

In keeping with CAHFS's outreach mission as a service center for veterinary public health, the tips below are specifically for our veterinary colleagues who are seeking professional guidance based on the findings of current research related to the prevention of AMR and prevention/treatment options for Salmonella.

Prevention

Large quantities of antimicrobials are consumed for animal health purposes in veterinary medicine for domestic animals and animal husbandry (the agricultural branch concerned with animals raised for meat, fiber, milk, eggs, etc.). Continued misuse/overuse of antimicrobials encourages development of strains of antimicrobial resistant bacteria, including AMR Salmonella strains. Once these strains emerge, transmission may occur through direct contact with animals, consumption of animal products, or contact with animal waste products in the environment.

Salmonella infections in animals are frequent and often asymptomatic; consequently, prophylactic use of antimicrobials is a common practice. However, preventing the infection in the first place is the most important way to keep the herd disease free.

Young animals are more susceptible to Salmonella infection and thus keeping different age groups separate is important. Young animals should also be fed and managed before older animals. It is important that contact between infected or ill animals and healthy animals is limited.

To preserve the antimicrobials we have and prevent more AMR and MDR Salmonella strains (among other AMR bacteria) from emerging, we must employ alternative infection control and prevention strategies. Since livestock is the most important reservoir of non-typhoidal Salmonella, judicious use of antimicrobials is essential in keeping antimicrobial resistance low.

What can animal health professionals do?

- Only give antibiotics to food producing animals & domestic animals to control/treat infectious diseases

- Regularly test animals for infections

- Ensure proper hygiene practices are maintained in animal husbandry

- Vaccinate animals to prevent to reduce need for antibiotics

- Research alternative infection control and treatment options

- Improve pathogen surveillance systems to track current and emerging AMR strains

- Implement tracking systems to track movement of sick animals

The following graphic, courtesy of the CDC National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria, demonstrates how antibiotic resistance can spread through animal and human populations.

Client communication

As with any other infectious disease, client communication and education is paramount in preventing disease transmission. Since MDR Salmonella poses a risk of zoonotic disease transmission to humans, farmers should be aware of the potential risks related to MDR infections in humans and especially in vulnerable groups such as children under 5 years old, elderly and immunocompromised people. Communication should be done in a language the client can understand.

One Health is a multidisciplinary approach to achieving optimal health for animals, humans, and the environment. The idea that these three sectors are intimately interconnected is not novel; however, this approach is seldom applied. A One Health approach entails eliminating barriers which prevent animal, human, and environmental health sectors from collaborating with one another.

Although there are isolated interventions in place already, to truly make an impact, large scale global interventions are required to address this ever worsening issue.

We live in a globalized society and now more than ever is the health of each sector dependent on the other two sectors. Populations continue to grow and spread, we have more contact with animals, and climate change is altering disease distribution and land usage. Ultimately, decisions individuals and institutions make in each health sector have large scale implications for all health sectors.

Currently we are facing a global public health crisis as antimicrobial resistance becomes more widespread. Addressing this public health crisis requires a multidisciplinary approach. Antimicrobial usage is not exclusive to one sector; consequently, the task of solving AMR does not concern solely one health sector.

Only through combined efforts of animal, human, and environmental health professionals and institutions will we be able to address the problem of antimicrobial resistance. AMR is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires tackling from multiple perspectives, in other words, it requires a One Health approach.

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), fighting antimicrobial resistance requires the following actions:

- Infection prevention

- Tracking of infections and treatment outcomes

- Improved antibiotic prescribing (ie. stewardship or judicious use of antimicrobials)

- Development of new drugs, treatment modalities and diagnostics

Public concern around AMR often focuses on risk and threat, with less focus on how public policy works to address those risks. Improvements on a societal level can be done both through the development of compulsory regulations and voluntary policies.

At CAHFS, we work to provide a holistic view of issues, like AMR, through our work in public policy. For policies to be effective, they must be put in place throughout the system: from grassroots to the global level.

The following document demonstrates some examples of policy interventions currently in place, starting from voluntary policies implemented by single entities like clinics or hospitals, and moving to regional or global programs. AMR and Public Policy

Some of the policies described in the document include:

- Voluntary local policies: Infection control programs, judicious use of antimicrobials

- National compulsory policies: Regulations to control antimicrobial use

- National voluntary policies: National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP), voluntary certification for biosecurity in Finland

- Global voluntary policies: World Health Organization Global Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance, FAO/OIE/WHO Tripartite Collaboration on AMR

- Global compulsory policies: World Trade Organization Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Agreement

Additional resources

Locally, nationally, and internationally there are a variety of organizations addressing AMR. However, only so much can be achieved without the support and engagement of the general public. Below are resources to educate oneself on this topic and learn how to contribute to the solution.

Minnesota Department of Health: Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Antibiotic / Antimicrobial Resistance

- Tracking Threats Using Data

- National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS)

United States Department of Agriculture: Antimicrobial Resistance Overview

World Health Organization

World Organization for Animal Health

- OIE Standards, Guidelines, and Resolution on antimicrobial resistance and the use of antimicrobial agents

- OIE-antimicrobial.com

Center for Animal Health and Food Safety: Multidrug-Resistant Organisms fact sheet

Content on this informational webpage was created with support from Cristina Zarama, MPH student, as part of her MPH project.

Additional support from College of Veterinary Medicine, School of Public Health, and funding from the Minnesota Department of Health.

Special thanks to Irene Bueno, Craig Hedberg, and Noelle Noyes.