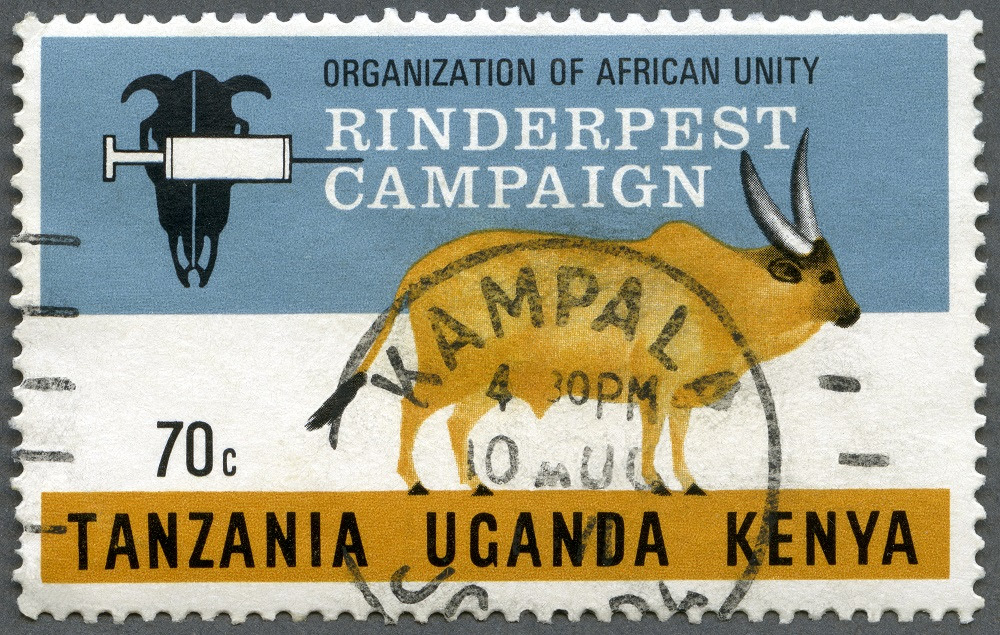

1971 stamp from the East Africa Rinderpest vaccination campaign

Historical background

Vaccination is one of the most successful and cost-effective health interventions ever developed. As all eyes turn to the recently announced COVID-19 vaccines, in this Weekly Topic we will dive into another side of vaccine development—veterinary vaccines.

Human and animal vaccinology have been inherently linked for hundreds of years. By the 16th century, variolation in humans was common in Europe. Variolation used smallpox sores from patients to expose other individuals who had never had smallpox to the virus (variola virus), who then contracted a mild form of the disease. Upon recovery, the individual was immune to smallpox. Simultaneously the same practice was being applied to lambs with sheeppox.

In the 18th century, scientists discovered the cross-protective properties of the vaccinia virus, which causes cowpox, to confer effective immunity against smallpox. This allowed for the safer practice of what was dubbed "vaccination" to become a standard component of human medicine. Two centuries later, in 1980, smallpox was declared eradicated from the world—so far, the only human disease for which we can claim that victory.

Thirty years later, in 2011, a similar success (that may not have received as much attention as smallpox) was declared by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rinderpest, the cattle-plague, was eradicated.

Both eradication programs relied heavily on an effective vaccine.

The current discussion in global forums is centered on a shortlist of diseases for which future eradication would be feasible, based solely on vaccination campaigns. This list includes some "usual suspects" such as polio and measles in humans, and the Peste des Petits Ruminants (PPR) and dog-mediated rabies in animals.

New challenges that veterinary vaccines could help address

Eradication is not the only, nor the primary goal when using most vaccines. In this broader context, veterinary vaccines (VVs) have had, and continue to have, a major role in protecting animal health and public health. This has been done by preventing animal suffering, enabling efficient food animal production, and tackling the prevalence of zoonotic diseases and food-borne diseases, among others.

Vaccines vs. antibiotics: the risk of antimicrobial resistance

A crucial advantage that VVs bring is the potential to reduce the need for antibiotics to treat animals, and this is especially important considering the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). A coordinated response is necessary in the face of the exponential increase in prevalence and geographic expansion of AMR across pathogens that affect multiple species (e.g., food animals, pets, humans, wildlife). In the last decade, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers (e.g., WHO, FAO, OIE) have shifted efforts towards achieving judicious antibiotic use in human and animal health. In this context, VVs are a strong contender as an alternative to antibiotics due to their effectiveness and feasibility.

Conceptually, VVs can prevent the development of AMR in two ways. The first is reducing the frequency of diseases in a population by preventing bacterial infections directly, or preventing a viral infection that facilitates opportunistic secondary bacterial infections. This would lead to a reduction in the use of antibiotics. Second, when coupled with efficient diagnostic tools, VVs support veterinarians to make more judicious use of antibiotics by helping to rule out certain pathogens as the cause of a disease.

Finally, there are scarce examples of pathogen resistance towards vaccines, compared to antimicrobial resistance. This may be due to multiple reasons: First, vaccines work, most of the time, in a prophylactic way, preventing the infection by reducing the susceptibility of the host to the pathogen, whereas antimicrobials are used therapeutically, working to control the infection that is already established. Second, effective vaccines are developed to elicit a robust immune response against multiple targets in the pathogen. In contrast, each antimicrobial targets a very specific component in the pathogen machinery.

Therefore, pathogens more easily evolve mechanisms to resist the action of antimicrobials than of vaccines. Gaining a better understanding of why AMR is more common than vaccine resistance may help make new vaccines as robust as their predecessors.

How do we unleash the full potential of veterinary vaccines in the field?

In order to establish effective and sustainable vaccination programs, reliable information on the burden of diseases and robust evaluations of vaccination programs are essential. Unfortunately, often the evidence is not available in the field of animal health. Many lessons can be learned from the human health field to apply economic tools to make the case of the value of VVs.

Expanding investments in the assessment of disease burden and vaccine effectiveness may catalyze the development and deployment of more effective VV programs.

Like any tool, vaccines are not magic bullets. Still, the onus is on the community of producers, veterinarians, policymakers, pharmaceutical industry, and researchers to enable a vaccine’s full potential. Veterinary vaccines are a key tool to relieve the burden of infectious diseases in animals, which remain a major constraint to sustained agricultural development, food security, and economic growth through international trade.